Alfonso Ossorio

Before the 1989 release of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography Jackson Pollock: An American Saga, few people outside of the upper reaches of the art world had ever heard of Alfonso Ossorio, the Philippine-born artist and collector who was Pollock’s close friend and most important patron. Ossorio died about a year after the book was published–he was buried in Green River Cemetery in Springs, N.Y., where Pollock is also buried–and interest in his life and art has been climbing steadily ever since.

Ossorio was, for nearly four decades, a prominent figure in the Hamptons, where he and his partner Ted Dragon lived in The Creeks, an Italianate mansion on the largest waterfront estate on Long Island. Harvard-educated and deeply cultured, Ossorio had considerable wealth and an aristocratic mien that tended to overshadow his achievements as an artist. During his lifetime, Ossorio’s reputation was shaded by the easy assumption that he was primarily a collector who dabbled in art, a well-heeled and eccentric “Sunday painter.” As a Philippine-born Catholic whose art drew from many wells–including medical illustration, Catholicism, gay sexuality, Surrealism and the art of the mentally ill–Ossorio was very hard to categorize. It didn’t help that his art was often characterized as “hysterical” and “bizarre.”

Alfonso Ossorio, Beach Comber, 1953, oil on canvas, 84 3/8 x 144 3/8 in.

Calling Ossorio an Abstract Expressionist–which at times he certainly was–creates a problem for art historians who see AbEx as a heroic American enterprise. Jackson Pollock: An American Saga made it clear that Ossorio was a key figure in Pollock’s life–as a friend, a patron, and a follower–but since then it has become increasingly evident that there is more to the story. Yes, Pollock influenced Ossorio and helped him break through into fresh artistic territory, but Ossorio also apparently later returned the favor and influenced Pollock. Some of Pollock’s late Black Pourings are now said to have “striking affinities” with earlier, semifigurative works by Ossorio.

Ossorio looked up to Pollock as an artist who “had broken all the traditions of the past and unified them, who had gone beyond Cubism.” Indeed, Pollock’s drip-based automatism gave Ossorio tools to access and grapple with his personal wounds and fantasies. The Victorias Drawings that Ossorio made in the Philippines during an extended stay in 1950 have been called his “breakthrough works” and have also been said to “share DNA” with the works of both Pollock and the French founder of Art Brut, Jean Dubuffet. In fact, Dubuffet was so enthralled by Ossorio’s works of the early 1950s that he developed a new form of art writing to be able to describe them.

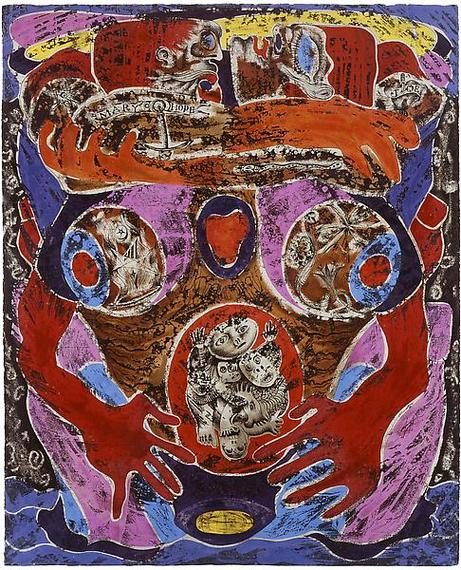

Alfonso Ossorio, Tatooed Couple (sic), 1950

Ink, wax, watercolor and gouache on paper, 25 1/2 x 20 3/4 in.

In 2013, the landmark exhibition Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet–originated at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. and curated by Dorothy Kosinski and Klauss Ottman–treated the three artists as peers, mapping their aesthetic conversation and locating stylistic interchanges. One tendency all three men had in common, according to The Wall Street Journal, was a “penchant for experimenting with unconventional materials and techniques, and a predilection for rawness over refinement.” During the same year, a solo show at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York–Alfonso Ossorio: Blood Lines, 1949-53–featured thirty-three works created during a seminal phase of the artist’s development, adding to the growing interest in Ossorio’s oeuvre.

In 2016, in celebration of the late artist’s one hundredth birthday, Manila’s León Gallery assembled the largest collection of Ossorios to be exhibited in the country– a total of sixteen works– all never before exhibited in the Philippines. Among them were some of the artist’s remarkable Victorias Drawings, executed with layers of wax, gouache, watercolor, and Chinese ink. It has taken time for Ossorio’s art to be fully appreciated in his home nation, even longer than it has taken in the United States. His varied works–always intense, often jarringly strange, and occasionally gruesome–were shaped by his youthful sexual turmoil and lifelong morbid fascinations.

***

Born in 1916 to a wealthy mestizo sugar baron and a Chinese-Filipino mother, Ossorio was one of six brothers born into an atmosphere of privilege: “It was a world of being taken care of,” he later recalled. His parents separated while he was growing up–his father moved to the United States–and Alfonso spent much of his childhood in England with his mother and two of his brothers, attending Catholic preparatory schools. The family would gather for summer holidays in posh European resort towns.

Ossorio then came to the United States as a teenager to attend the Portsmouth Priory from 1930 to 1934. Portsmouth Priory was a Benedictine high school run by monks in Providence, Rhode Island. Ossorio became an American citizen in 1933 and then in 1934 began his undergraduate education at Harvard, where his mentors and friends included Eric Gill, Philip Hofer, Lincoln Kirstein, and Paul Cadmus. Although his father disapproved, Ossorio majored in fine art, completing a thesis titled “Spiritual Influences on the Visual Image of Christ.” During summer studies with Eric Gill in Sussex, England, Ossorio did research on medieval art and created wood engravings. After graduation he briefly studied at the Rhode Island School of Design, painting in tempera. Discovered by the famed art dealer Betty Parsons, he had his first show–of fastidiously rendered, Surrealist-tinged images–at the Wakefield Gallery in 1940.

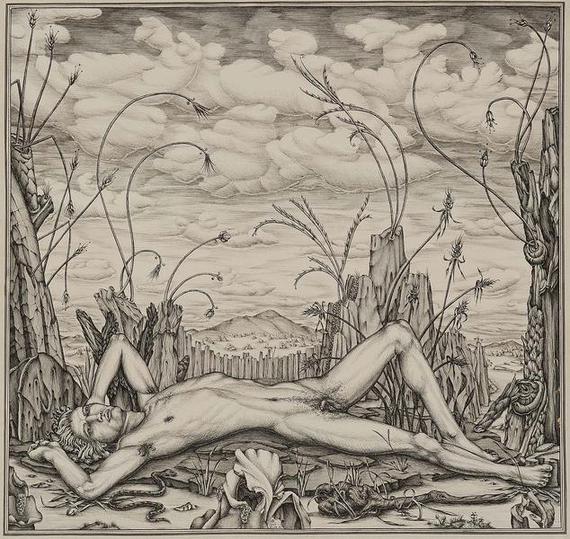

Alfonso Ossorio, Young Moses, 1941, ink on paper, 17 3/4″ x 18 3/8″

A brief marriage, to a divorcee that his parents disapproved of, dissolved a month after Pearl Harbor, and fate soon appeared in the form of a taxi that hit him on Madison Avenue, breaking his leg. “As a result,” Ossorio later explained, “I didn’t get into the army until the spring of 1943. I don’t know how much use I was in a military sense, but they took me and kept me in. I ended up in a general hospital doing medical illustration.”

While stationed at Camp Ellis in Illinois, Ossorio was assigned to draw surgical procedures, many of which were very graphic and gruesome. He stood on a ladder, looking down on surgeries that often involved grievous war injuries suffered by soldiers, and sketched the procedures. After his discharge from the army in 1946, these macabre visions would invade and influence his art. In the summer of 1948, while vacationing in The Berkshires, Ossorio was sketching flowers in a meadow when he met a 25-year-old ballet dancer, Edward (Ted) Dragon, who was there picking nosegays. They moved in together the following year and remained devoted to each other until Ossorio’s death in 1990.

Around the same time, Ossorio also had his first encounter with the paintings of Jackson Pollock–which he at first thought were too messy–and soon afterward, he made his first purchase:

You see I hadn’t met Pollock, and it was simply by going to Betty’s gallery and seeing a show of his. I think it was as late as 1947 or ’48 that I suddenly realized the so-called drip panels had an intensity of organization, had a message that was expressed by its physical components, was a new iconography. I didn’t get all of this as coherently as I’m now saying it–it was a visual thought more than an analysis. And then I bought a painting, a big panel 8 x 4, of Jackson’s.

Ossorio and Ted Dragon soon met Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner; Ossorio’s Pollock needed some repairs and Pollock essentially gave it back to him as a new painting. A close friendship blossomed between the couples–Ossorio spent the summer of 1949 at the Pollocks’ home in the Hamptons–and the timing was fortuitous, as Pollock was making some of the best work of his career and staying away from drinking. At Pollock’s urging, Ossorio then met and visited the artist Jean Dubuffet in Paris, where the two had an immediate and significant connection. With his exposure to Pollock, Krasner, Dubuffet, and to a lesser degree, Clyfford Still, Ossorio now was surrounded by a constellation of ambitious, advanced artists, and in this situation his own art was set to blossom. Critic John Yau says that between 1949 and 1953, Ossorio “seemed to find his place in the world.”

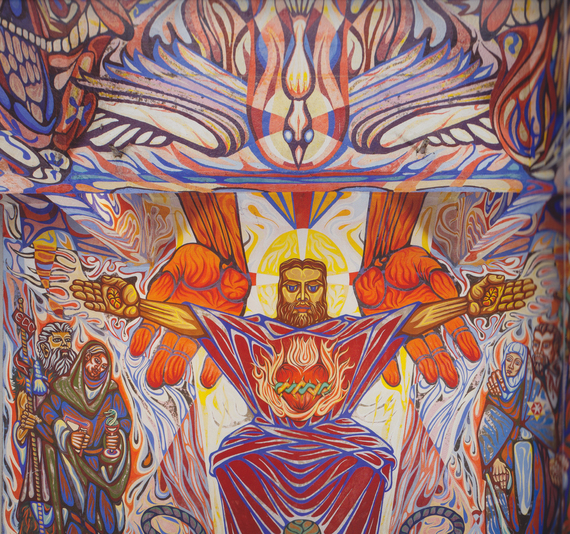

Detail of Alfonso Ossorio’s The Last Judgment (Angry Christ)

Photo via Art After War: 1948-1969 by Patrick D. Flores

In 1950, Ossorio returned to the Philippines at the request of his father; he hadn’t been there since the age of ten. Working with untrained assistants, he spent ten months in Victorias City painting a 36′ x 20′ mural that Life magazine later dubbed “The Angry Christ.” A searing and radical image that offers a stylized vision of The Last Judgment with the Holy Spirit and an army of angels dawning on the world in critical transition, it was tolerated by the community largely because Ossorio’s influential brothers were in charge of the project.

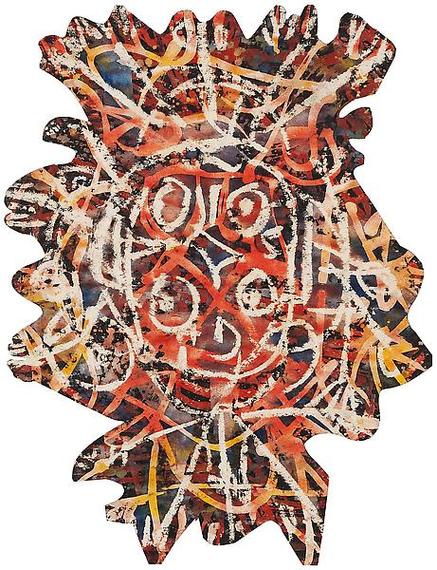

Being in the Philippines opened up feelings of personal turmoil for Ossorio, whose sexuality conflicted with the values of his devout Catholic upbringing. Artistically liberated by the examples of Pollock and Dubuffet, Ossorio poured his feelings into a series of works, now known as the Victorias Drawings, that dealt with childhood, birth, sexuality, mythology, and religion. Executed with a wax resist technique, the series was drawn on Tiffany stationery, which was then often cut into irregular shapes that rhymed with Ossorio’s fantastic imagery. Hybrids of recognizable figuration and all-over abstraction, the Victorias works have phenomenal psychic energy: an aura of spiritual and supernatural intensity. Although Ossorio has occasionally been characterized as a “lapsed Catholic” that is not at all the case. The intensity of the Victorias Drawings is grounded in faith and religious conviction. Ossorio believed that “if you want to be serious, there is very little that is not religious.”

Alfonso Ossorio, Foursome (A Four-Headed Game), 1950

Ink, wax & watercolor on cut & shaped Tiffany stationary paper, 11 1/4 x 8 5/8 in

So in the summer of 1951 this opportunity came to buy the place I’m now living in, the old Hearst place in East Hampton. I had accumulated a number of pictures all of which were sitting either in my father’s home or bank. I bought it but didn’t move to East Hampton until the summer of 1952. I’ve been there ever since even in the winter. And apart from a few trips to Paris and Turkey and Greece I’ve done very little traveling since.

Fernando Zóbel de Ayala, another wealthy Harvard-educated artist who was also a distant cousin, visited Ossorio at The Creeks in 1955 and recorded his impressions in a vivid diary entry:

Spend most of the night talking with Alfonso Ossorio; in fact, between the two of us, we finish a whole bottle of scotch, and I get into bed at 4:30 in the morning. We talked mainly of painting and of being a painter. The gist of his remarks, repeated over and over again with variations and a kind of anguish: “Don’t let them stop you.”

He (Ossorio) lives and paints at high pitch, burning the candle at both ends. He is spending and living on his capital…. Loathes compromise, any attempt to popularize. “Art must be difficult to see, difficult to understand.”

Ideally, he would like to see people forced to choose between buying an automobile and buying a painting. About 10 years older than I, unquestionably good, with a desperate, Dostoyevskian sort of goodness. Completely generous, completely humourless. Inflexible and full of pratfalls. Completely committed to his art, which, for him, is an extension of religion.

His visit with Ossorio left a lasting impression and is a clear source of inspiration for Zóbel’s Saetas series of the mid-1950s, which employed paint ejected from hypodermic syringes to create dynamic webs of abstract imagery. Through Zóbel, Ossorio’s embrace of Pollock’s modernism would eventually influence notable artists in both the Philippines and Spain.

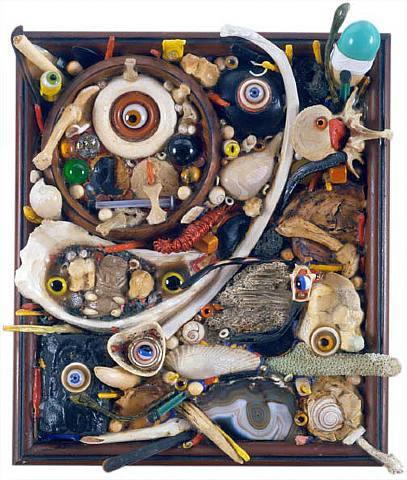

Alfonso Ossorio, Forearmed, 1967, mixed media assemblage

Through the ’50s and into the ’60s, Ossorio continued to exhibit his own work, his Pollocks, an Art Brut collection and other works he had been collecting. The Creeks was jammed with continually rotating pieces of art. Splendid candlelit parties, attended by artists, opera singers, and dancers, filled the rambling forty-room mansion. Guests ogled each other and the modern art–displayed on black walls alongside arrays of African masks, exotic caged birds, ivory dragons, and Ossorio’s growing display of assemblages (which he called Congregations) made from found objects: detritus, bones, sheet metal, driftwood, and more. In the years that followed, bright geometric Ossorio sculptures appeared on the grounds, indicators that the artist had, in some sense, mellowed.

Ultimately, Ossorio is best seen as an individual and as an artist who held on to his differences while both finding inspiration in the works of his friends and disseminating their influence. In a late interview, when discussing his relationship to Abstract Expressionism, Ossorio offers his career as “an obvious case of admiring and doing differently.” He continues to explain that he “chose other freedoms” and remarks that “similar freedoms can lead to different results.” Writer Lee Rosenbaum has something similar to say: “What I think of Ossorio–the artist speaking in his own distinctive voice–is the ‘outsider’ work of this art world insider.”

Alfonso Ossorio truly was, as Fernando Zóbel observes at the end of his 1955 diary entry, “gorgeously out of touch with reality.”

Image Credits:

The works of Alfonso Ossorio are presented with the permission of the Ossorio Foundation