Austrian-born Roland Strasser (1885-1974) was an artist, writer and world traveler who explored remote areas of Asia before the cultural transformations wrought by modern warfare and air travel forever altered their local customs. An adventurous spirit who packed a revolver and often dressed like the locals when he traveled, Strasser explored China, India, Indonesia, Mongolia, New Guinea, Japan and Tibet, covering some 30,000 miles in the process.

Many of Strasser’s most admired paintings were made in Bali, a place that he found enchanting. At the end of his travels he and his wife Enrica were sequestered in their Bali home from early 1942 through late 1945, hiding from the occupying Japanese: they went nearly four years without seeing any other Caucasians. In October of 1945, two months after Japan’s surrender, AP war correspondent Hal Boyle found Strasser and Enrica holed up at their mountain home in Kintamani and offered the artist his first American cigarette in a decade. “Bali has changed terrifically since I first came here in 1919,” Strasser opined between puffs: “These people are losing their gods.”

Strasser was one of the six children of Arthur Strasser and Maria Dorothea Strasser. Professor Strasser, who had French Basque bloodlines, was a leading Viennese sculptor known for his exotic bronzes and hand-finished polychrome ceramics. A Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, Arthur Strasser created the spectacular cast of the obese Roman Emperor Marc Anthony in a chariot pulled by lions that still stands on a concrete base next to the Viennese Secession gallery. Upon first seeing the newly installed sculpture in 1899, socialite Alma Mahler wrote in her diary: “Strasser is the most monumental artist I’ve ever seen.”

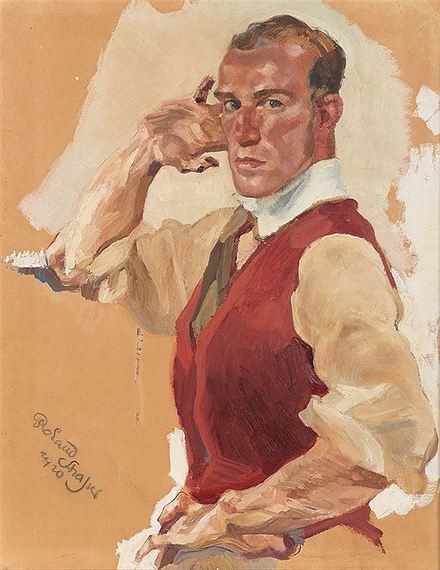

At the age of 17 Roland Strasser accompanied his father on a trip to Egypt: it left a lasting impression and whetted the young artist’s appetite for travel. After studying sculpture at the Academy of Art in Vienna, where his father was a faculty member, Strasser enrolled in the Munich Academy in 1911 and studied painting with Angelo Jank, a specialist in equestrian and historical scenes. Along with his older brother Ben, who came to Munich in 1913, Strasser then worked for the Imperial war press as an official war artist. His grim, and highly realistic canvas After the Battle remains in the collection of Vienna’s Museum of Military History, a reminder of the young artist’s first hand exposure to the horrors of modern warfare.

Photo: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Vienna

Strasser worked as a lithographer and book illustrator at the close of the war, and then took his first “study trip” to Holland to paint in the picturesque fishing village of Volendam on the Zuiderzee. It was there that he first heard about the virgin beauty of the Dutch East Indies, which must have offered a striking contrast to the turmoil that gripped postwar German and Austria. A successful exhibition of the paintings made in Holland funded Strasser’s first journey to Indonesia, beginning in December of 1919. The first stages of the trip included four months in the interior of Dutch New Guinea where Strasser, abandoned by his guide, sketched the members of a gentle tribe of Papuan natives who posed willingly. He then meandered back to Java, visiting Borneo, Celebes, Flores and Timor.

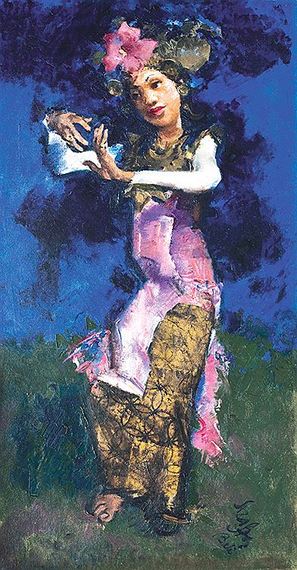

“Ah, what a rainbow,” Strasser later told an interviewer. “The Batak Highlands of Sumatra, the Sultanate of Djokja, Solo in Java and the island of Bali. Little-known, it seemed like a perfect dream, content in its commerce with the heavens, deep in the awareness of its people, and quite oblivious to Occidental questionings and speculation.” Strasser was enchanted by Bali and its “graceful wealth of everyday life” and stayed there for a year and a half.

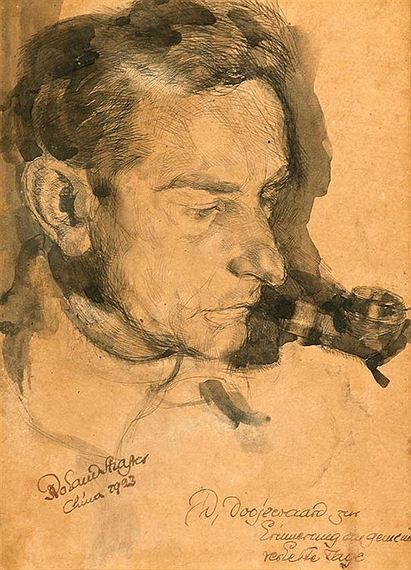

The paintings he made during this first stay in Bali, including an oil of a ten-year old Legong dancer named Pitja, are boldly colored and brushed. Although he had been trained in academic methods, the sensuality and beauty Strasser found in Bali unlocked his sense of formal experimentation. It was also in Bali that Strasser met the Dutch artist Willem Dooijewaard who became a close friend, student and frequent travel companion.

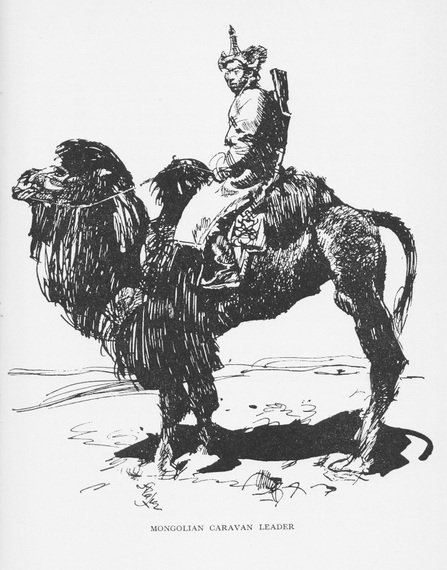

After a 1922 exhibition in Java, presided over by Dr. Fock, the Dutch colonial governor, Strasser left for China. Traveling by way of Hankow to Peking, he then entered the edge of the Mongolian plateau via Changkiakow and began his stay by living in a yurt among nomads. Later, while traveling with a Chinese-Mongolian interpreter who had introduced himself as a “Christian by profession,” Strasser observed and painted Mongolian festivals and Lama cloisters. Strasser, who viewed Mongolia as a “kaleidoscope of color, a fairytale in life and sprit,” returned to Europe with a collection of a works made in China, Japan, and Mongolia that were exhibited to glowing reviews in London. Sales netted him 4,000 pounds sterling, the current equivalent of nearly a quarter-million dollars. In the years that followed, Strasser’s London agent, William P. Paterson, continued to successfully manage the artist’s business affairs in his absence.

In December of 1924 Strasser embarked on series of journeys that would last several years, beginning in India and ending in Japan. He stayed ten months in Tibet, aided by a guide who had been a member of the first Mount Everest expedition and spent a year in Urga, the capital of Outer Mongolia: while in Urga, Soviet officials arrested and detained Strasser as a spy, confiscating his diary and maps, but allowing him to keep his paintings and drawings.

In 1926, after making his way through the Gobi desert with boxes of art, he crossed into China and experienced a disastrous loss: In Peking, 180 of his artworks were destroyed by looting Chinese soldiers. Still, there were enough works remaining for shows in London, Paris, Vienna and Berlin. Returning to Vienna after his father’s death in October of 1927, Strasser married Enrica Luise, a charming equestrienne who he lured away from another suitor. She too was a painter, until a Viennese critic recommended that she stop. During this period Strasser worked on a book, The Mongolian Horde, illustrated with numerous pen and ink drawings. Since Strasser’s diary had been confiscated during his recent trip, the text came from his memories.

“I can give no special reason for having undertaken such a journey,” he writes in the book’s forward. “By this tramp of five years through Asia I wanted to justify my rights as a human being and, under boundless skies, without any set purpose or limitation of time, to come into contact with Nature herself with courage and endurance, and without negation.” A riveting, pessimistic travelogue that is full of memorable descriptions, The Mongolian Horde alternates between descriptions of the region’s starkly beautiful landscape and the unforgettable appearances of some of its inhabitants. In a chapter titled Wandering Strasser describes coming across a skeletal, naked Tibetan draped in entrails, wearing a sheep’s stomach as a hood and holding the slaughtered animal’s heart in his hands.

Strasser also details the superstitious nature of the Mongolian people. While working on an oil portrait of a Mongolian princess, he became frustrated when his modeled opened her garment to nurse a child, revealing “purple spots and warts as large as peas.” After using a palette knife to scrape her features from the canvas in progress, Strasser soon heard a rumor from locals that he had put the picture under the influence of “evil spirits” by removing the woman’s face. He left on a Chinese cart the next evening to escape the curses and wrath of the woman’s lama husband.

Published in New York, London and Berlin, The Mongolian Horde bolstered and broadening Strasser’s reputation. “It will have historic value,” noted one reviewer, because it records with the insight of a trained eye, the incoming tide of superficial Westernism…” In 1929 Strasser and Enrica spent a year in Kyoto, Japan where he painted and drew kabuki performers, sumo wrestlers and geishas. Strasser proudly recounted that the Japanese had a high regard for artists, and that he would sometimes find audiences of sixty to seventy people watching him when he worked on location.

After a variety of treks in the early 1930s, including more time in Indonesia, the Strassers settled in Kintamani, Bali in a home with spectacular views of the lake formed in the caldera of an active volcano: Mount Batur. When Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merpres, a Belgian painter who arrived in 1932, was asked why he chose Bali, he responded: ‘There are three things in life I love. Beauty, sun and silence. And could you tell me where I can find a more perfect version of those things in any other place than Bali?’ The Strassers, who sought the same things, moved to Kintimani to avoid the growing crowd of artists, tourists and sexual adventurers who were appearing in the town of Ubud and hour away. When tourists came to Kintimani and knocked on the Strasser’s front door, hoping to purchase paintings, he often avoided them by escaping through a secret back door.

After the Japanese arrived in early 1942, ending Dutch colonial rule, life in Bali changed considerably. By the time the Japanese left Bali grinding poverty, Christianity spread by missionaries and growing nationalistic fervor had re-shaped its culture. The Strassers laid low during the occupation, depending on locals for food and assistance: “It was a time of great difficulty,” Enrica later recalled, ” but the Balinese were very kind.” It was also a lonely time, particularly for Enrica, who occupied herself by tending two horses, a monkey and seven dogs. “Yes, it is beautiful,” she told Hal Boyle, “but have you ever looked at the same beautiful things for ten years, morning, noon and evening?”

Assisted by Australian troops, the couple left for Sydney in early 1946 after Roland destroyed 30 paintings. He brought with him the text of an unfinished romance that was never published. The world had changed and so had they: Strasser was now sixty, and his health had been compromised by bouts with tropical diseases and the privations of the war years. The demand for exotic travel paintings had declined as color magazine photos now provided the glimpses of faraway lands and peoples that painters like Strasser had once provided so he turned to portraiture.

Although they hoped at some point to again live in Vienna, the couple never managed to return to Europe. After several exhibitions in Australia, by the early 1950s the Strassers had settled in Santa Monica, California where the mild climate was easy on Roland’s health. Strasser exhibited his art, taking part in exhibitions in Long Beach and Laguna, and also restored a 1930s mural by the Mexican master David Alfaro Siqueiros.

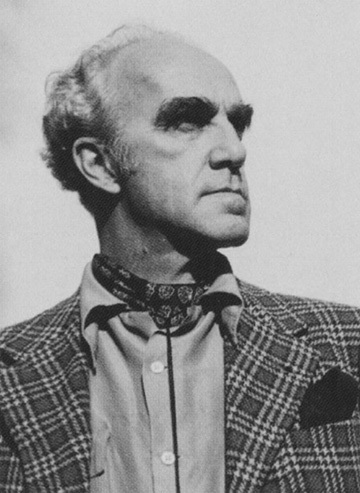

When Janice Lovoos, a writer from American Artist visited Strasser’s Santa Monica apartment in 1960 she described the strong impression he made:

“He has a strong visage, with heavy brows, a shock of white hair, and penetrating, deep-set eyes that are at once sad and wise, and at times filled with good humor.” Lovoos described the Strasser’s apartment as “bulging with canvases” and noted that Roland had his studio in a refurbished room where he could “shut the door and work.” When he spoke to Lovoos about his time in Bali, the aging artist’s memories came alive:

What I found in Bali was of quite a different character: the soothing inducement of a delightful language and charming people. Here, the nights were ablaze with distant stars and always full of the syncopated music of the Gamelans… It was truly fascinating to work and live among the graceful wealth of everyday life.

Acknowledgements:

Images of Roland Strasser’s paintings appear with the permission of the Roland Strasser Estate.