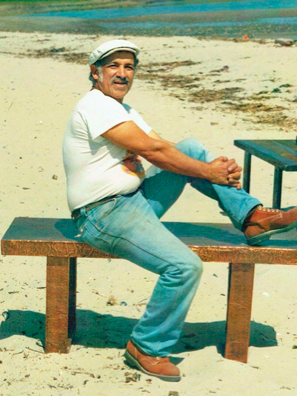

Born in Puerto Rico, Frank Diaz Escalet moved with his family to Greenwich Village at the age of four. Growing up in poverty, he drew his own comics (he couldn’t afford comic books) and by the age of 14 was delivering ice and firewood, often lugging them up flights of stairs in the hopes of a nickel tip. After dropping out of school after 8th grade to help support his family by taking factory jobs, Escalet joined the Air Force in 1947 and was deployed to England. There, he unloaded American ships during the Korean War, working along the Irish dockworkers of Liverpool with whom he felt a sense of camaraderie.

Escalet married in 1953 and left Air Force duty the following year to return to New York. The marriage, which produced two daughters, was quite brief, ending in in divorce in 1955. In New York Escalet’s first job was at a garage where he changed tires and pumped gas. It was there that he met a man who drove a 1941 Plymouth that had been converted into a pickup truck filled with hand-made copper tables and lamps. Fascinated by the contents of the truck, Escalet asked the man if he would teach him metalwork and the answer was “yes.” After a brief apprenticeship Escalet quickly progressed from copper to silver, opening a “hole in the wall” jewelry shop called “The Talent Shop.”

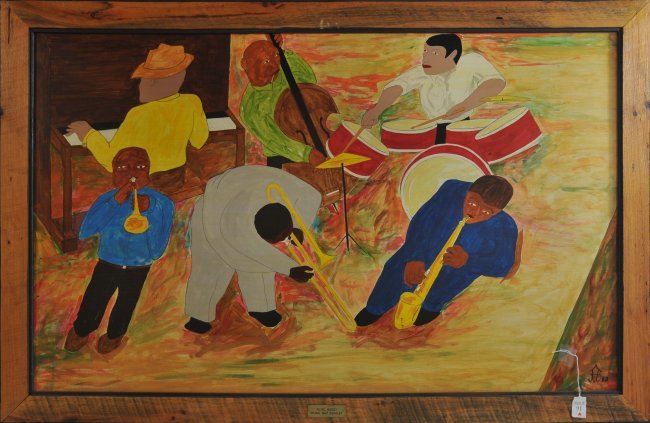

With his strong work ethic and skilled hands, Escalet quickly developed into a successful craftsman who was able to gradually expand his business. Realizing that leather was going to be more profitable than silver, in 1958 Escalet opened a leather specialty store—“The House of Escalet”—that soon prospered and attracted clients including Aretha Franklin and members of the Rolling Stones. The noted cellist Pablo Casals once commissioned Escalet to make him a custom cello case and he also did specialty work for the Museum of Modern Art. In 1964 Escalet married his second wife Marjorie, an artist. Together, they renovated an $80 per month loft with rosewood floors in the Bowery above Chinatown. “It was a wonderful place to live,” Marjorie later remembered. “He (Frank) always went out, had a few beers and listened to jazz.”

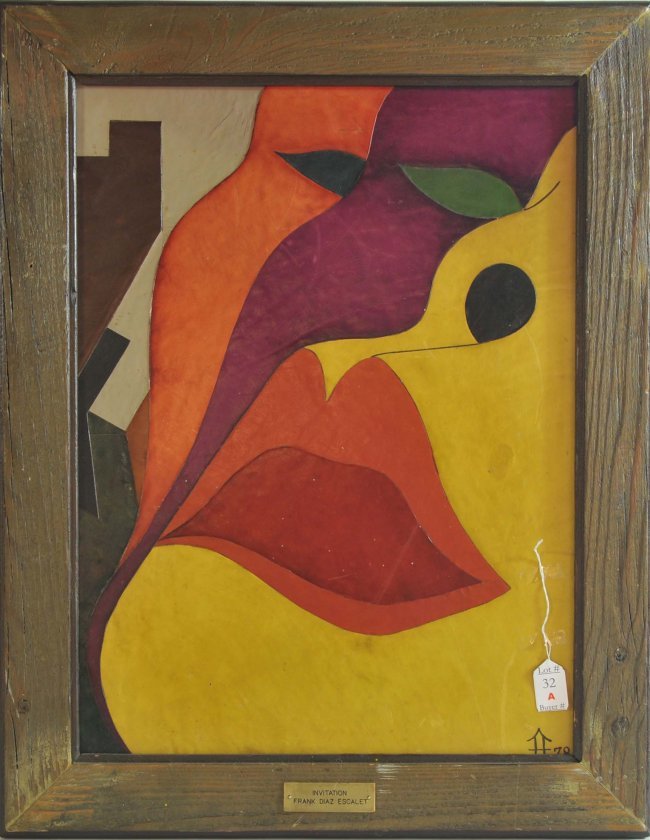

Escalet, who often worked seven days a week, now had five employees and growing responsibilities. Three years after the birth of their son Frank Jr. (Danny) in 1968 the Escalets moved to what they hoped would be a safe and affordable town to raise their son in: Eastport Maine. Frank soon opened a store called “Pandora’s Box,” and earned extra cash by teaching leather-craft at the nearby Pasamaquoddy Indian reservation. By 1974 he was creating works of art crafted from carefully cut and inlaid pieces of colored leather. These works, strikingly individualistic and made with a medium rarely used by fine artists, were the opening act in Escalet’s gradual emergence as an artist.

Escalet’s first works in leather were bold, simple and stylized. One series was based on motifs and ideas taken from African art while others were inspired by everyday life. Working with leather required Escalet to lay out clearly defined forms with edges that could but cut with a sharp knife and locked into carefully planned compositions. The fact that Escalet had not received formal art training did not hold him back and living with Marjorie—an artist who had some training and who worked in oils—had rubbed off on him. Leather was Escalet’s breakthrough medium and it also established his sense of difference from other artists and artisans.

As Escalet’s artistic career grew, his family life was moving towards tragedy. His son Danny was being consistently bullied—even tortured—at school by classmates who saw him as different. After a few years of disturbing incidents the Escalets sued their local school district and won an out of court settlement. “You can’t educate people who were that ignorant,” Escalet later recounted. The deep scars left by bullying and abuse were profound enough that Danny, who had become a drug abuser, took his own life in 1984.

Shattered by his son’s death, Escalet took solace in his work. Escalet began to call himself a painter, re-dedicating himself to his artistic development. He moved to Kennebunkport and established a studo and gallery that he called “The House of Escalet,” and established himself in his new community. The hard work paid off and sales and critical recognition grew. As one critic later noted, Escalet was a storyteller who could be thought of (in some respects) as a kind of Hispanic Norman Rockwell:

Like Rockwell he (Escalet) depicts his neighbors, friends, and associates. Like Rockwell he portrays the poignancy of their hopes, dreams, and sorrows with compassionate insight. There the similarity ends, for Escalet is a Latino cantadora: his tales, therefore, colorful as they are, are laced with the bitter taste of poverty and enslavement.

In 1989 Escalet was the subject of a 30-minute episode of La Playa—a program that showcased Hispanic culture—broadcast by an affiliate of PBS Boston. In the film, Escalet’s humility and candor are very apparent: so is his reliance on intuition: “As I am sketching,” he offers, “I don’t look at the sketch so much. I ask myself ‘does it feel good,’ and then I know I’m on the right track.” The film ends with Escalet driving the streets of Kennebunkport in a burnt-orange Chevrolet that he rescued from a junkyard and kept running for ten years, another indicator of his resourcefulness.

In 1990 some 135 works by Escalet were featured in a traveling one-person show that opened in Prague and traveled to seven other countries in a “World Peace Tour” that lasted for five years. More attention—in the form of awards, magazine articles and a one-person show at Penn State—established Escalet as a leading Hispanic artist. When his exhibition “Hopes Dreams and Sorrows” opened at Amherst University in 2006 a local critic called Escalet, now 76 years old, “one of the most talented artists out there today.”

When Frank Escalet died in 2012 he left behind a positive legacy. His art—which is inventive, large-hearted and sincere—continues to tell the stories that he gleaned from his life and from history. Escalet was driven to be creative and worked hard in a variety of media to find meaning. If anything, his greatest asset was his curiosity, an unstoppable force that moved his career forward at the most difficult moments. “With curiosity,” he once said, “you are looking at and discovering things. You can take off like a bird.”

Do you have artwork by this artist that you are interested in evaluating or selling?

INQUIRE ABOUT YOUR ARTWORK