Zhang Daqian

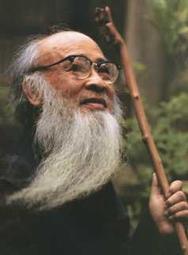

Between November 16th and December 17th of 1972, the 74 year old Chinese artist Zhang Daqian (aka Chang Dai-chien) was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition in San Francisco at the Center of Asian Art and Culture (now the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco). It was a triumphant event for the aging artist who had been living in Carmel since 1968, and whose artistic output had been affected eye problems that had plagued him since the late 1950s. A first experimental eye surgery in 1969 had actually worsened the sight in his right eye and the artist had taken to wearing glasses with a darkened right lens. However, a 1972 surgery to remove his clouded left eye lens had restored 20/40 vision in that eye, allowing Zhang to see color with the help of glasses. Within a few months he was painting again.

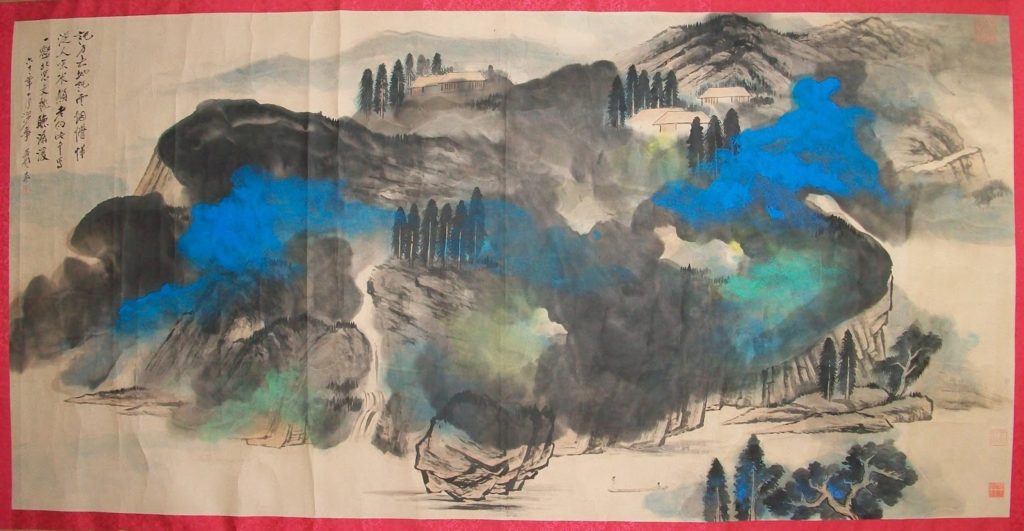

One work made in this era—very likely for the San Francisco exhibition—depicts the scenery around the lake in a park near Zhang Daqian’s Carmel Residence “Huan-Bi-An.” It also includes imagery of the famous “17-Mile Drive,” a scenic road through Pebble Beach and Pacific Grove on the Monterey Peninsula. If the scene looks characteristically Chinese, it should be noted that one of the reasons Zhang had moved to Carmel was that it’s pine trees reminded him of China. Flowing through the center of the painting’s boulders and pines is a semi-abstract river of bright blue and turquoise color. The color is evocative, although it is not clear whether it might be mist, water or a manifestation of abstract energy. The painting carries an inscription and dedication to the artist Mi Fu (米芾, 1051-1107), a scholar, poet, calligrapher, and painter of the Song Period known for his mastery and eccentricity.

The “splashed color” style was something that had been an important part of the Zhang Daqian’s output for more than a decade. Originally made in response to diabetes-related eye problems, which made it increasingly difficult for him to see fine detail, Zhang first developed his mature splashed color (pocai, 潑彩) style in Europe, beginning in 1956, and then continued experimenting it when he moved to Brazil. Zhang said that this style derived from the “broken-ink” style of Tang Dynasty artists, but it can also be readily compared to Japanese “Splashed Ink” paintings of the Muromachi Period, especially those of Sesshū Tōyō (1420-1506). Comparisons to American Abstract Expressionist and Color Field paintings, including the stained abstract landscapes of Helen Frankenthaler, also work well.

When working on larger pieces Zhang had assistants who would move the rice paper while he worked. Once he observed the desired flow and interplay of water, ink and colors, he would tell his assistants to stop moving the paper. Zhang’s splashed color paintings employed a variety of media, often including distemper, an ancient medium often found in Buddhist “thangka” or scroll paintings of deities. Consisting of mineral and chalk pigments suspended in animal collagen glue, distemper creates bold, flexible areas of matte color and somewhat resembles gouache (tempera). As in the 1972 Carmel landscape, the abstractness of the splashed color works in both in concert with and in contrast to recognizable imagery painting in dark ink.

When San Francisco art critic Alfred Frankenstein reviewed Zhang’s 1972 exhibition, he wrote that the splashed color works in the exhibition felt “both ancient and modem at once … original and decidedly up to date.” He also noted the distinctive and transformative role these works had played in the artist’s development: “One feels that Chang Dai-chien (Zhang Daqian) came into his own only when he shook off the weight of the ancient dynasties he had carried for so long on his shoulders.”