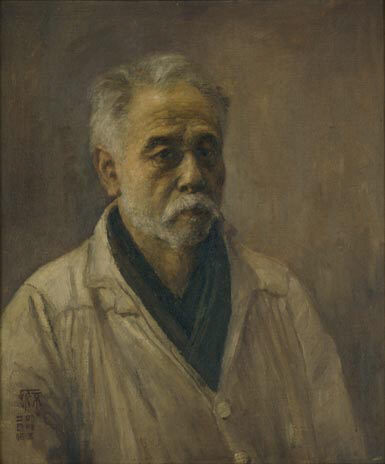

Xu Beihong, "Self-Portrait" (Berlin)

Xu Beihong: An Introduction

Xu Beihong (aka Hsü Pei-hung) was a Chinese painter whose lifelong project involved re-invigorating Chinese art by hybridizing it with Western influences. Motivated by his conviction that the tradition of Chinese painting had gone slack and that over-reliance on mimicry of the past left Chinese art unable to carry the necessary messages of modernity, Xu Beihong saw himself as a modernizer and reformer. In his 1918 article “Improvement Methods for Chinese Painting,” he advised: “Retain the good ancient methods, revive the moribund, correct the bad, strengthen the inadequate, and integrate those elements of Western painting that can be used.” By traveling and living in Europe after World War I Xu Beihong was able to make a career out of following his own advice.

Despite his overt commitment to modernity, Xu Beihong’s artistic taste favored the Academic Realism that he was first exposed to as a student in Paris after World War I. Throughout his mature career as an artist and as an educator, Xu Beihong extolled the academic value of drawing from life. Although his palette eventually reflected a restrained Post-Impressionist approach to color, he condemned the works of Van Gogh, Matisse and Cézanne, which he said lacked content. In a essay he wrote entitled “Doubts,” Xu Beihong argued:

Despite the mediocrity of Manet, the vulgarity of Renoir and the superficiality of Cézanne and the ugliness of Matisse and all the evil of these opposing trends, they still managed—with the help of art dealer’s manipulation and propaganda—to become the sensations of their time and dazzle the general public.

On the other hand, Xu Beihong had an abiding respect for Old Masters and while in Europe made convincing copies of works by Jordaens, Rembrandt and Velasquez. Accordingly, the style Xu Beihong eventually became associated with—Socialist Realism (會主義現實主義 Shehuizhuyi xianshizhuyi)—was powerfully shaped by the French Academic tradition and by the artist’s encounters with the European masterpieces that he viewed during his European travels.

Xu Beihong’s Early Life

Xu Beihong was born Xu Shoukang in Jitingqiao, a small riverside town 200 miles west of Shanghai. His parents originally named him “Shoukang,” which means “longevity and health,” but as a struggling young artist he re-named himself “Beihong” meaning “sad wild goose.” His father, Xu Dazhang, was a painter and calligrapher who had fallen on hard times and supported his family by growing watermelons. Because the family had no money to send him to school Xu Shoukang studied the classics with his father, who also taught him traditional Chinese painting. Water buffalo, geese and horses appear in his early ink paintings.

When a flood damaged their town, the young artist and his father became itinerant artists, painting portraits and landscapes and carving seals. During their travels, young Xu Beihong saw reproductions of European paintings that piqued his interest. After his father fell ill and died, the nineteen year old artist traveled to Shanghai where he failed to find employment as an illustrator. Desperate and suicidal, he sent one of his horse paintings to the noted artist Gao Jianfu, who responded enthusiastically: “Even the ancient Han Gan could not have done better than this.”

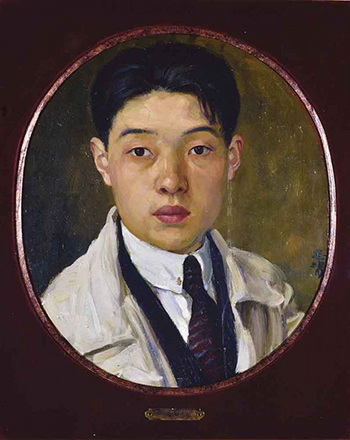

After then taking the entrance exam for Shanghai’s Aurora University, he borrowed tuition money and entered college, studying French and painting. He soon impressed local authorities with a large watercolor portrait of Cangjie, the legendary inventor of Chinese characters, and was given a position as a painter and lecturer at Mingzhi University. Like most intellectuals of his generation, Xu Beihong fell under the spell of Chen Duxiu, the founder of the very popular journal “New Youth,” and later a co-founder of the Communist Party of China. Chen’s proposal for a “Revolution of Art” and his promotion of Western values over Confucian values helped motivate Xu Beihong and many of his peers to study Western art and culture.

Xu Beihong in Japan: 1917

In May of 1917 Xu Beihong made his first trip outside of China. Using funds earned from his portrait of Cangjie, he eloped with 18 year old Jiang Biwei, who was escaping an arranged marriage. Although Xu Beihong would have preferred to go to France, the continuing war in Europe altered his plans and the couple boarded a steamship for Japan. During his visit Xu Beihong took every opportunity to view public and private collections where he paid special attention to examples of Western style art. He also met and interacted with Nakamura Fusetsu (1866–1943) a painter, calligrapher and book cover designer who had studied in Paris. The couple had originally intended a longer stay in Japan, but Xu Beihong was an avid collector who spent lavishly on works of art, draining their budget and forcing the honeymooners to return home after just six months.

Upon Xu Beihong’s return to China he began teaching at Peking University’s School of Art at the invitation of Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培), the university president. Cai Yuanpei was well known for his critical evaluation of Chinese culture and also his interest in synthesizing of Chinese and Western thinking.

At Peking University Cai Yuanpei assembled influential figures in the New Culture and May Fourth Movements and also supported the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement, which sent worker-students to France. In March of 1919, with the blessing of Cai Yuanpei and a small stipend, Xu Beihong and Jiang Biwei left for Paris.

Xu Beihong in Paris: 1919-21

They arrived on May 10, 1919 after a week in London, then spent several months visiting art museums. Xu then enrolled in the Académie Julian—which was regarded as a stepping stone to the prestigious Ecole Des Beaux Arts and had no entry requirements—to study drawing. Like many other Chinese in Paris, including the future leaders Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, who lived in a flat near Place d’Italie, Xu Beihong and his wife found themselves impoverished and living in cramped conditions. Xu Beihong eventually suffered intestinal spasms as a result of malnutrition and a bread and water diet. Paris was a city of an estimated 70,000 artists and art students and because the French economy was just beginning its recovery from a catastrophic war, Xu Beihong had arrived at a difficult and transitional moment.

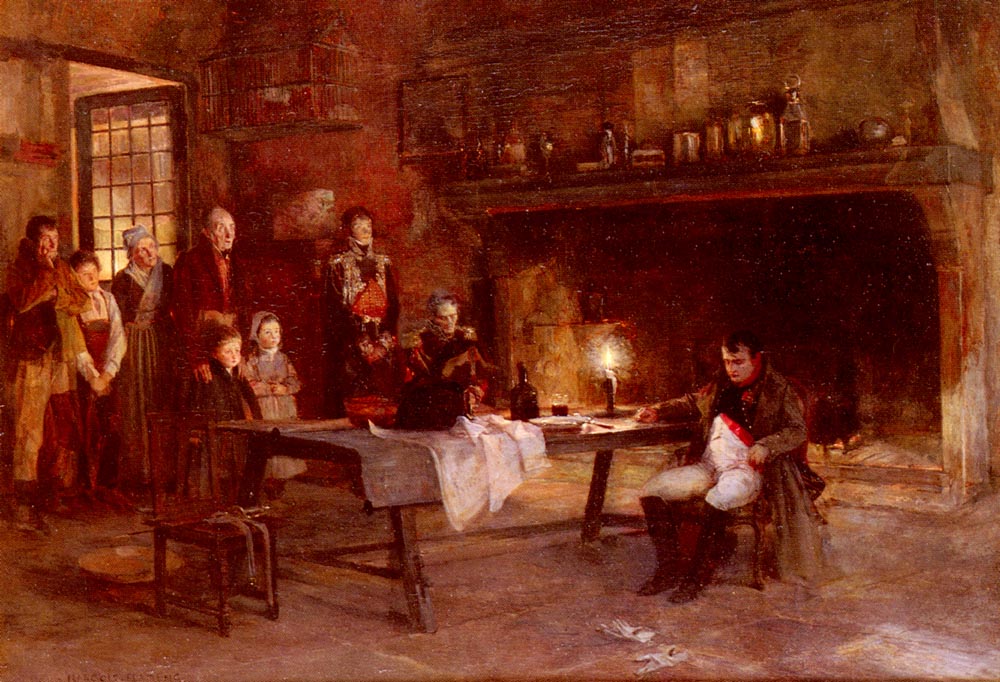

After passing the entrance exam of the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Xu Beihong first studied with François Flameng, the institution’s president and also the president of the Société des Peintres Militaire Français (The Society of French Military Painters). A pupil of the painter/historian Alexandre Cabanel, Flameng was best known for historical pictures—including bloody revolutionary epics—and fluidly brushed society portraits. A proud man who was exceedingly aware of his social position, Flameng once wrote: “Those of us to whom generous nature has accorded the artistic gift—a genius or simply talent—are the lucky ones of this world.”

Xu Beihong also studied privately with another artist who became a kind of father figure, Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929). A student of Cabanel and Gérôme, Dagnan-Bouveret was known for his peasant scenes, often set in Brittany and also for his mystical-religious compositions. His large-scale painting “The Last Supper” had been exhibited at the Salon de Champ-de-Mars in 1896. A friend of the American portraitist John Singer Sargent, Dagnan-Bouveret was capable of detailed realism, and was one of the first academic artists to endorse the use of photography as an aid to painting. He reportedly told Xu Beihong: “The matter of art is most difficult. One should not follow fashions nor be satisfied with small accomplishments.”

Xu Beihong in Berlin: 1921-23

In 1921 the Chinese government suspended the scholarships of Chinese students abroad, adding further stress to the artist’s situation. He and his wife traveled to Berlin, hoping that their French francs would go further in the inflation-wracked Weimar economy. In Germany, Xu Beihong met Arthur Kampf (1864-1950), a history painter who was the president of the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. A member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts, Kampf later became an early joiner of the Nazi party: his name was eventually included on the “Gottbegnadeten-Liste”(God-gifted list) of artists considered crucial to Nazi culture. During his 20 months in Germany Xu Beihong painted images of lions in the zoo and made copies of works in German museums, including one of Rembrandt’s 1656 Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Xu Beihong’s Return to Paris: 1923-25

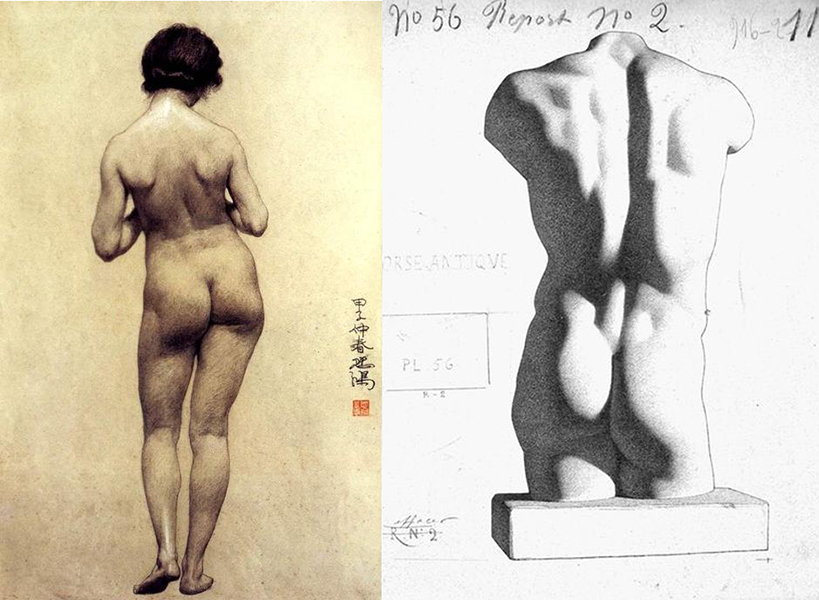

The restoration of his scholarship in allowed Xu Beihong to return to Paris in 1923, where he resumed studies with Dagnan-Bouveret. As his drawings from the period show, Xu Beihong was now a capable draftsman, whose studies of nudes reflected the careful structuring and sense of observation recommended by the leading French artists of the time. It is very likely that he was trained using the lithographs published in the classic Drawing Course (Cours de Dessin) of Charles Bargue and Jean Léon Gérôme that had been published in Paris in the 1860s and 1870s.

Xu Beihong’s return to Paris was a productive moment that brought him his first significant recognition. Nine of his paintings were included in the Salon of 1924, and when he returned home by way of Shanghai in 1925 he was given portrait commissions and then had a successful one-man exhibition in Shanghai. An additional visit to Europe, which included a return to Paris and the opportunity to view Michelangelo’s frescoes in Rome brought Xu Beihong’s roughly eight years of foreign travel and study to a climax.

Seen in China as a Europeanized “Bohemian”—he returned home with long hair and a velvet coat—Xu Beihong had absorbed the same artistic traditions that vanguard European artists of the era were questioning and rejecting. It is important to consider that in the same year that Xu Beihong first visited Paris (1919), that the Bauhaus—Europe’s first school dedicated to modern art, architecture and design—was founded in Dessau, Germany.

Xu Beihong had taken little to no interest in the dissolution of form or inner-directed themes taken up after World War I by the European Avant-Garde. In fact, he may have recognized that some of the abstract tendencies of European Modernism overlapped with the imaginative stylizations in the Chinese tradition that he was intent on updating.

Instead, he infused the ancient (and to his view moribund) aesthetic of Chinese painting with scientific perspective and chiaroscuro. By doing so, he was able to compose epic scenes of modern Chinese history that shared the grandeur of European precedents. The dramatic lighting and varied poses of Xu Beihong’s “Tianheng’s Five Hundred Heroes” endow it with a level of conviction and power that could not have been realized without the artist’s in-depth exposure to European painting. Xu Beihong took from European art precisely what he needed: verisimilitude and structure.

Xu Beihong was a shrewd artist who knew that if his work was convincing the Chinese people would find it memorable. When he organized a promotional tour for Chinese art in 1933, the exhibition’s “gouha” (Socialist realism that embodied current ideologies) must have already appeared passé to many Europeans. Of course, what looked advanced in Shanghai necessarily looked familiar in Paris, where a young Chinese painter had once strolled in its museums and learned from an aging cadre of academically trained masters.