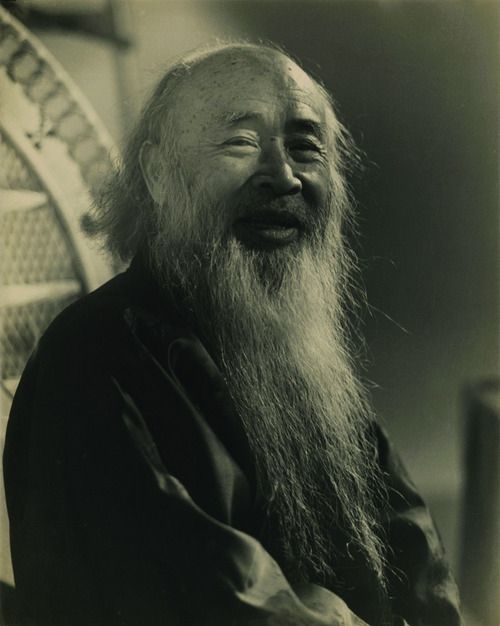

Judging Zhang Daqian (aka Chang Dai-chien) as an artist isn’t hard to do: he was a versatile, daring and highly accomplished painter. Judging Zhang Daqian as a man is much more difficult, as he was a dedicated forger who paid for his extravagant lifestyle by creating absolutely convincing copies of ancient Chinese paintings and duping collectors into buying them. “He had 100 different styles, some original some not,” says critic Paul Richard.

Simply labeling Zhang Daqian as “colorful” risks serious understatement. The father of at least sixteen children who was married to four wives simultaneously, Zhang Daqian kept uncaged bears and panthers on his ranch in Brazil, cultivated 100 plum trees on his Monterey estate and was a powerful figure who had close ties to Chiang Kai-shek, the head of the Chinese government on Taiwan. After a Taiwanese consular official once refused to give four of Chang’s wives new passports simultaneously, he found himself transferred to Swaziland, where he died in a car accident. Described by one writer as “a bandit, a Buddhist monk and a playboy,” Zhang Daqian’s original works have recently brought stunning prices at auction, while his forgeries—which lurk in museums and private collections across the world—continue to give curators and art historians headaches.

In Western culture “forger” carries and immediate and damaging set of connotations. In China, where art education has always emphasized copying and even slavish imitation of ancient masters, there is a more complex and fluid set of values concerning artistic imitation. In fact, there are three levels of copying that have been traditionally tolerated and even encouraged, especially during an artist’s education:

Fang:

Taking styles, tropes and methods from an artistic school, style, or famous master and rearranging them into a fresh composition.

Mo:

The copying of canonical paintings so as to juxtapose the skill of a living artist with the skill of an old master.

Wei:

Forgeries in the Western sense made with paper and seals that are intended to fool collectors and appear authentic.

According to one account, a youthful Zhang Daqian made his first forgery to gain attention, a ploy that worked. He created a hanging scroll in the style of the 17th century master Shitao and titled it “Through Ancient Eyes.” It was, in the context of the categories mentioned above, a “Fang” or improvisation in the style of a master. After an art collector praised and purchased it, calling it one of the “finest works by Shitao he had ever seen,” Zhang revealed his authorship of the scroll. The collector, although embarrassed, didn’t stay angry for long: he now owned an impressive copy by an artist who was rapidly becoming famous.

The lesson gained from this experience, that creating forgeries could both humble and impress collectors, stayed with Zhang Daqian throughout his life. Also, in Chinese culture there has long been a “buyer-beware” attitude prevalent in art transactions, coupled with the notion that buyers should be connoisseurs who can discern just what they are purchasing and that dealers can be held harmless since they are just presenting material for inspection.

Complicating matters is Zhang Daqian’s great productivity: he produced an estimated 30,000 works over his lifetime, of which roughly 5,000 have been catalogued. It’s impossible to say just how many of his remaining works, involve some degree of imitation or forgery. Also, Because Zhang Daquian opposed China’s Communist regime, and left the mainland in 1949, many of his works were likely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. One of the ways he supported himself, while living and traveling in India, Hong Kong, Argentina, Brazil, California and ultimately, Taiwan, was the production of forgeries.

For this reason, museum curators across the globe always ask themselves, while studying what are purported to be examples of classic Chinese painting: “Could this be by Zhang Daqian?” Since one expert believes that at least every major collection of Chinese painting contains a forgery by Zhang Daqian, the answer might indeed be “yes.” Crossing ethical lines and playing many roles, Zhang often doctored or “improved” ancient works, created seals that perfectly mimicked those of ancient artists and forged or altered documents related to works of art. He even played the role of art dealer and then boasted about fooling dilettantes and naive collectors.

Zhang Daqian was also a collector himself, who amassed three significant painting collections: the first contained Song through Qing Dynasty masterpieces, the second was works by Shitao, and the third featured works by Bada Shanren. Significant examples from these collections now reside in museum collections.

By most standards Zhang Daqian engaged in behavior that Western courts would judge as criminal. By his own standards, he was a Daoist “trickster” who outwitted pompous fools and separated them from their money. He was also a “living master” who—in his own estimation—equalled or surpassed the artists he venerated.

For a number of reasons, Zhang Daqian has often been called the “Chinese Picasso,” and in many respects the label fits. Cunning, versatile and hedonistic, Zhang Daqian achieved great fame and became to China what Picasso was to Europe: an icon. Picasso was also a destructive artist who absorbed the tradition he had been born into and then attempted to destroy it. Zhang Daqian was also destructive but in a very different fashion: he insinuated himself and his work into a very ancient tradition, and did it with such aplomb that his works and the works of his masters may never again be accurately differentiated.